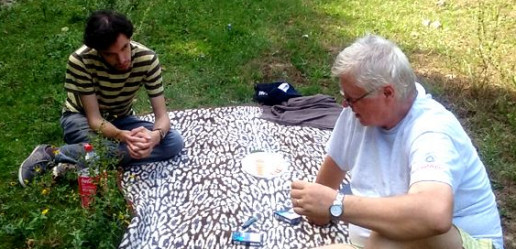

Two rounded backs discussing music, Sohodol Valley, 2015. Mastermind Dan Aldea (left) liked

to call himself "a serious man." "Shatter-brained, and yet serious," he'd continue.

"There are two kinds of musicians : happy and sad. Stevie Wonder is happy," Aldea once told me. "One must be a very happy person to accept a shitty arrangement like I Just Called." "What about the two of us ?" I asked. "Us ? Definitely sad." Aldea was a major influence on me as a musician, and I was fortunate enough to be his friend. He introduced me to musical semantics and encouraged me to be uncompromising at work. I've written several texts about his music (see details here).

my formal education

In a nutshell : my folks sent me and my brothers to some of the best schools in town. We studied at St. Sava national college, which remains to this day the highest-ranking secondary school in Romania.

In 2006 I switched gears, however, and entered the National University of Music to study composition and jazz. Up to that moment, I'd self-taught myself music theory for many years ; I had been able to obtain most of the necessary textbooks.

My bachelor's thesis dealt with Dan Aldea's early work — much like an investigation which set out to understand some of the professional decisions he took as a teenager, and outline their effect on his further career. In 2016 I returned to university for a master's degree, this time joined by my wonderful collaborator Diana Zăvălaș. Our goal was to determine to what degree can jazz-like improvisation fit the world of Argentine tango, a genre that we've been exploring together for several years (see below).

Some of the teachers who've left a strong mark on my work are : Gheorghe Lăzărescu (literature), Mircea Tiberian (jazz), Liviu Dănceanu (history of music/æsthetics), Dinu Ciocan (semiotics/semantics), Octavian Nemescu (electronic music). Dan Buciu was also an indirect influence ; while I never attended his classes, the two-tome volume Tonal Harmony he published in the 1980s had a considerable impact on my perception of the European musical tradition.

composer v/s arranger

In 2010, my composition output as a self-made Stravinsky came to a halt. The prospect of fulfilling another wish seemingly mattered more : after a long unsuccessful attempt to find adequate poetry in my native Romanian, I now got the chance to collaborate with writer Alex Tocilescu, whose moralistic, yet radio-ready literature I truly admired.

My initial thought with poetry was to compose a Lieder cycle. I must've been eager to hide meanings in plain sight, given my then-new-found excitement for semantics. Working with Tocilescu, however, confronted me with a major trade-off : as an amateur musician, he'd already penned melodies and chords for every single poem he had. I soon realised that my only option was to write arrangements of the existing songs and, at the very most, get involved as a composer when the song structures felt unsuitable or just too simplistic. While apparently easy, this was a hell of a job for me, and it proved to be unsuspectedly exciting once things started to take shape.

·

A couple of years later I came across a Stanley Kubrick interview, namely his famous 1976 talk with French critic Michel Ciment. What struck me was this piece of dialogue :

ciment :You have abandoned original film music in your last three films.

kubrick : (...) However good our best film composers may be, they are not a Beethoven,

a Mozart or a Brahms. Why use music which is less good when there is such a multitude of great (...) music available from the past and from our own time ?

My worry was that Kubrick stated a truth feared enough to be generally suppressed, and that his remark was applicable to all music, not just film scores. Soon after, I witnessed Dan Aldea saying more or less of the same thing ; then I remembered reading a clever joke about mediocre composers in George Enescu's memoirs. No wonder that my æsthetic intentions were to become even more radical than before, arriving at a new question : "Which music is worth making ?"

A good place to start would be the topic of absolute music ; but personally, it never moved me in any way. I remember watching Leonard Bernstein on TV back when I was ten, the charming experiment wherein he used Richard Strauss's Don Quixote as incidental music for a made-up Superman story, in order to prove that literary narratives are unessential for music. Well, all I could care about was how the story was made into music ! My compositions have always looked for some kind of company — be it lyrics, a concept or visual imagery — the essence of which, in return, enciphers to musical abstraction. Even in my "neoclassical years" I would deliberately use free association so as to make the composition incidental to my thoughts, no matter whether they were musical or not.

As for arranging, it's really the same, except that instead of a film or play there is a great melody to write incidental music to. Now if the melody happens to be less than great — or the film, the play — forced salvation may be an option too, but it comes with a price. And I don't mean the money.